Watts Towers

In light of the President fanning the flames in LA for his nefarious agenda, here’s my earlier blog about how the Watts Towers stood tall, despite being built by a man who was not even 5 feet tall and with no formal architectural background. Sabato Rhodia built a miniature Statue of Liberty, a beacon to all the minority communities in Watts. It stayed untouched by the Watts Riots, averted its demolition by the City of Los Angeles, the Rodney King Riots and survived multiple earthquakes. Named Nuestro Pueblo (Our Village) by Rhodia, it’s a fanciful cathedral where all are welcome, rising above the strife and is still standing today.

* * *

A non-descript white van with no side windows reverses and barreled back towards us. We were standing on a narrow road that dead ends just past the Watts Towers. Our rental car was parked ahead of us, blocked by the approaching white van, and unreachable for a getaway. Making it more menacing, the white van had a loudspeaker mounted on top, broadcasting an incomprehensible and relentless voice, like an enraged version of Charlie Brown’s teacher. And to make it even more mysterious and unnerving, all the yelling coming out of the fuzzy loudspeaker was in Spanish. My heart pounded a bit faster as the van got closer, not understanding really any Spanish, and trying not to let on any of this to my 17-year-old son. I turned around to see what was behind us for a possible escape. There I find a yellow END sign. Past the sign, there was a tall brick wall, and behind it, abandoned railroad tracks. This isn’t the first time I’ve been faced with this uncertain moment, having visited these Towers several times over the years in the heart of Watts.

* * *

When visiting Watts Towers for the first time, there was no official tour guide, in fact it was eerily vacant when I parked my car next to it. I was already a bit nervous, being out in South LA by myself. Just uttering the word Watts conjured a visceral reaction, especially with white people who didn’t live in that LA neighborhood. Hollywood has its Walk of Fame, the Grauman’s Chinese Theater and the headquarters for Scientology. Beverly Hills has its movie stars, the Menendez Brothers and OJ Simpson. When you say Watts, the immediate reaction is of the 1965 riots for anyone who didn’t live there.

It all began when a white cop hassled two Black men for being potentially drunk. Their mother got involved and so did other friends, family members and neighbors. Some were beaten with batons, and many others were handcuffed on the spot including their mom. The crowds watching grew larger and increasingly more agitated. It was a rerun of a movie the Black community had seen for decades—the long and unchanging history of police excesses, the lack of basic services like proper hospitals and schools. They were stuck behind an invisible but very real line between themselves and the rest of LA. That night in Watts, everyone in the neighborhood had had enough. Five days later, 34 people died, thousands injured, and thousands more were arrested with property damages running in the 10s of millions.

This was not my privileged white reality when visiting the Towers in the late 1980s. There was no invisible line stopping me. Whatever images the word “Watts” conjured; I had a false sense of invincibility, coupled with a genuine curiosity. I was willing to take the risk to witness this singular architectural creation some had called the eighth wonder of the world.

The Towers were built by Sabato Rodia, an Italian immigrant no more than 4 ‘11, barely 100 pounds, and with a limited education. Diminutive in stature, he aspired to big things. Sabato saw himself like the Italian greats; Michelangelo, Galileo, and Marco Polo. Like Marco Polo, Sabato embarked on a 30-year voyage. After a few failed marriages, he bought a small triangular piece of land in Watts in 1921 and spent 30 years building this unparalleled ship-like environment that pointed back to his homeland in Italy.

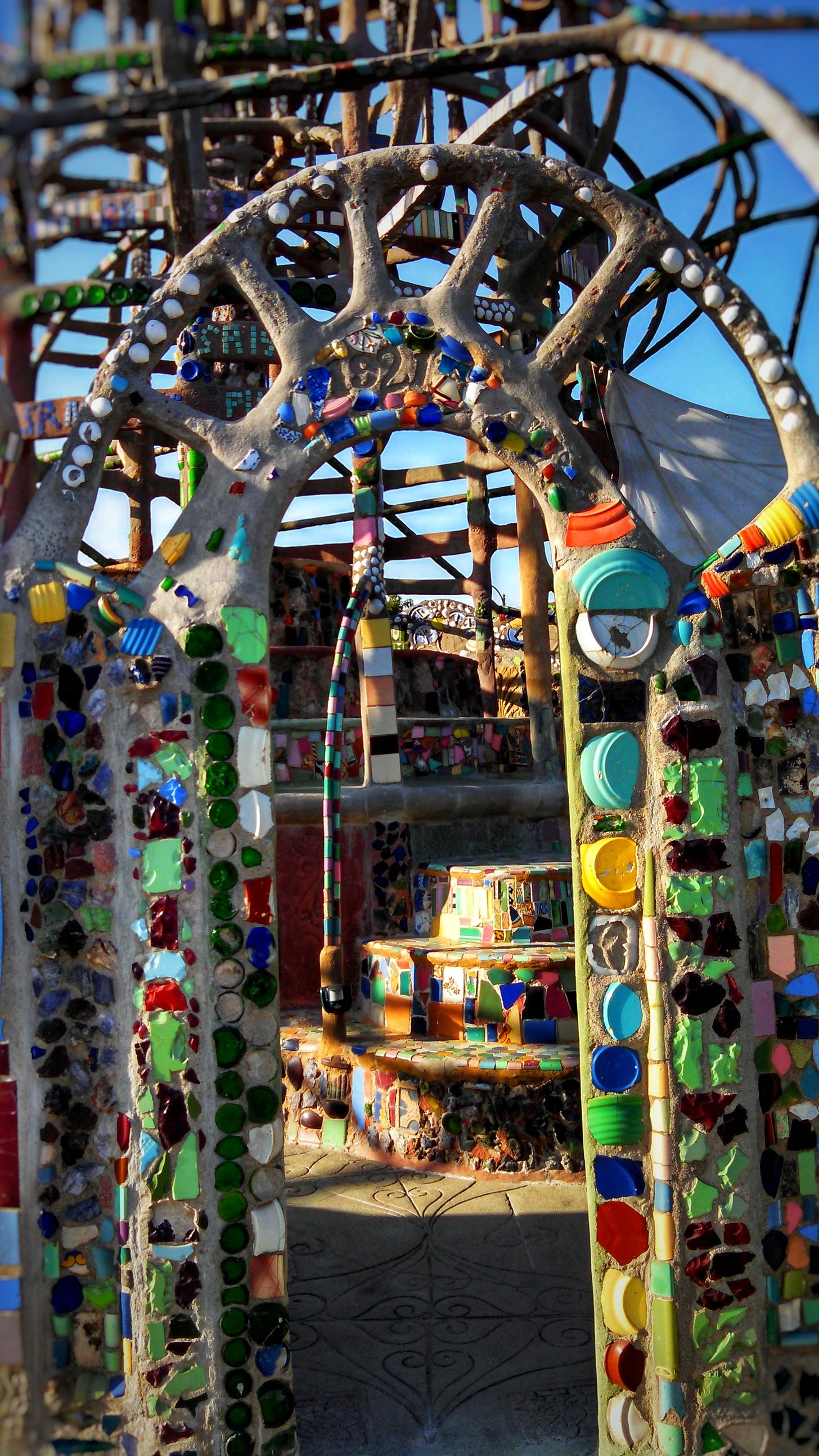

He used no bolts, no rivets nor did he weld anything. He didn’t even have a ladder. He merely waited for each level of wire mesh, steel and mortar to dry, then proceeded to stand on it and work on the next level. It was all in his head, with no drawn-up plans. He worked alone, only seeking help from the neighborhood kids who he paid to scavenge for discarded bottles on the nearby train tracks. He’d then break the bottles, adding them to the walls as tiled decoration, along with a myriad of other found objects like seashells, scrap metal and Fiesta Tableware.

During the day, he worked as a tile worker throughout LA. When returning home, his real job started every night, working every Sunday and on Christmas, sleeping only 4-5 hours. He named it “Nuestro Pueblo” or “Our Village” in Spanish to reflect the heavy Latino population in Watts at the time. This miniature Statue of Liberty became a beacon to all the minority communities in Watts. It remained untouched by the Watts Riots, averted by a multitude of calls for its demolition by the City of Los Angeles and survived multiple earthquakes. This fanciful cathedral where all are welcome, rose above the strife and remains to this day.

With all these superlatives in my head, I drove south into the unknown and crossed that invisible line below downtown LA. It wasn’t easy to find, unlike the countless highway signs and advertisements for Disneyland a mere 25 miles away. It was in a poor working-class neighborhood that was rebuilt in varying degrees after the 1960s riots, while remaining segregated for those with brown and black skin. Ten blocks away, I spotted the Towers jutting out like heroic beacons, like Lady Liberty out in the New York harbor, cutting through the LA smog and the countless utility poles.

Hesitantly, I circled around the perimeter, as there was a high chain-link fence around all the Towers, forbidding anyone to enter. Each wall is filled with mosaics of brightly colored broken tiles, mirrors, and the green bottle ends of Sprite and the blue bottle ends of Milk of Magnesia. Along with the colored decorations, Sabato hand drew in flowers and hearts on the walls; while making imprints of the tools he used into the cement too. He signed his architectural masterpiece with a simple handwritten “SR,” on the wall.

No one quite knows how Sabato got his inspiration and architectural ideas. Perhaps the towers were reminiscent of the giant sailboat masts in the Naples harbor near where he grew up? Or was he inspired by the festival in Nola, where each year the townspeople constructed 100-foot towers made of paper mâché called Gigli Spires? Whatever his influences, we’ll never know. Whenever Sabato was interviewed, he was known to change the story for whoever his audience was. Someone from the LA Times misidentified him as “Simon” in an article. Sabato didn’t feel the necessity to correct the reporter, then later became mistakenly known as Simon or Sam to everyone. This was of no concern to him. His concerns were his Towers and working night and day. Not one for wearing gloves, he worked so hard that his fingerprints had rubbed off and were no more. Whatever drew him to start the Towers in the 20s, he then abruptly sold it to his neighbors in 1954 for a modest amount. He packed up and moved to Northern California to be near his sister. Like his lack of fingerprints, he would never be seen in Watts again.

I left too, feeling a small victory as a modern-day explorer.

* * *

My second pilgrimage came two years later, this time convincing my grad school friends to take a break from our studies. They paused too when I said "Watts” was our destination. Still, my enthusiasm won them over and we went for a drive.

We never did make it to the Watts Towers that day. A mile before we even reached the spot, a police officer pulled us over.

“Are you from around here?” the cop interrogated us.

“No, we live in Hollywood. We’re on our way to the Watts Towers,” I sheepishly said.

“Well then, you need to get the hell out of here. Turn around, right now.”

We’re all shocked by his bluntness. Why were we being singled out? Was it because I drove a red Ford Falcon, red being the rival color of one of the warring gangs? It was obvious that we were pasty white hipsters in thrift store clothes, never to be mistaken for either a Crip or a Blood. The officer gave us no explanation. With resolve on his face, he impatiently waited for us to turn around and drive back to Hollywood.

No sooner did I make a U-turn at an intersection, than I had to suddenly swerve out of the left lane. Something had blocked the lane in front of us. Up ahead on the left median, a car was on fire. And by “on fire,” I don’t mean that the car’s engine had overheated, and smoke was billowing from the hood. No, when I say the car was on fire, I meant the car was on fire. And by this point, it barely looked like a car anymore, more like a smoldering metal skeleton. As we passed it, we could absolutely feel the heat from the flames. Later I would learn our naïve road trip coincided with what the LAPD was calling 1988, the “Year of the Gang.” A year with a daily onslaught of violence and death in Watts between the two gangs.

* * *

In 2015, when I toured the Towers again with my oldest teenage son, Watts had mellowed. There were no burning cars and no riots. Even after the 1992 Rodney King riots, Watts remained calm after four white officers were acquitted for using excessive force on a Black man. After ten tumultuous years, with too many of their own being killed, the Cribs and Bloods signed a truce the day after the riots started. Where much of LA was burned and looted, the Watts neighborhood and its Towers remained untouched.

Instead, there were now highway signs indicating when to exit for the Towers, welcoming 40,000 visitors each year. The inside was now open to the public. On entering this mad gingerbread-like cathedral, you realize there aren’t just three towers, but 17 of them at varying heights. Each tower is interconnected with crisscrossing buttresses up and down each tower, and each buttress is adorned with hearts. There are brightly colored tiled benches to sit on, gazebos to get married in, a fountain used for baptisms and a mini tiled replica of one of Marco Polo’s ships.

All this seemed of little consequence, as the van had almost reached us, and we had no place to go. The van’s maniacal loudspeaker was deafening. I turned to my son, hoping he could translate, but his high school Spanish comprehension had little use in discerning this scratchy loudspeaker voice. Various nefarious scenarios ran through my head. I had visions of gang members busting out of the back end of the van, taking our money. Even worse, they’d throw us in the back of the van and take us to some unknown location. I kept these scenarios to myself. I tell myself, it’s just my irrational and neurotic white imagination. Still, I ready myself to hold our ground, waiting in front of the yellow sign that read END.

The van finally stopped a few feet from us. The voice on the megaphone cuts off, only to be replaced by some fast-paced mariachi music. Our hearts start to beat as fast as the horn section plays. A Mexican gentleman jumped out of the driver seat of his van, walked by us, and straight to the backdoor.

He opened the door, and we hesitantly stared in. No gunman came busting out, no guns a blazing, no masked gang members were looking to abduct us. Rather, in the back of his van we found two metal bakery racks. The man nodded to us, pulls out the various shelves and reveals an abundance of Mexican pastries. On each level of the racks, there are different delicacies to choose from, a smorgasbord of brightly colored pan dulces, many laced with powdered sugar. He handed us each a white bag. In Spanish, he listed each pastry while pointing to them with his metal tongs. Our language barriers had no trouble interpreting the pastries in front of us. The conchas seem to be shaped like a seashell, filled with chocolate or vanilla. The cocada is the Mexican equivalent of a macaroon. And the orejas look like elephant ears. We pointed to our desired pastries. He grabbed them for us with his tongs. He then dropped them into our white bags, producing a little white cloud of powdered sugar rising out of the bag.

“Gracias," we say to the man after paying, then walked back up the road to our rental car.

And it was just in time. Not for a quick getaway, but to make room for the Watts neighbors. Many had heard the same megaphone voice and mariachi music and had now begun to line up in front of the van. Nuestro Pueblo lives on. We nod to the people from the neighborhood as we pull away in our car. With powdered sugar smiles, we drove back to Hollywood.