Bottle Village

"Anybody can do anything with a million dollars—look at Disney. But it takes more than money to make something out of nothing and look at the fun I have doing it."

—Tressa Prisbrey, from her self-published brochure for Bottle Village.

When I lived in LA in my 20s, part of my “A” tour for guests was not to take them to the top of the Matterhorn at the Magic Kingdom or to see the parting of the seas from the Ten Commandments at Universal. Rather, it was to drive up 45 miles north of LA to Simi Valley. Ok, so this town isn’t on anyone’s list of top ten things to do in sunny CA. Right off the bat, Simi Valley is a warm and dry inland town surrounded by many fault lines, making it easily susceptible to both wildfires and earthquakes. It had the dubious reputation of being the city that acquitted the officers who beat Rodney King by an all-white jury, a decision that ignited the fires of the LA riots. It is the only conservative city in Ventura County and was the perfect spot to break ground for the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library and Museum in 1987. The library was originally slated to be built elsewhere on the prestigious campus of Stanford University. But with strong opposition, and with the insinuation that such a library would force this institution to rebrand themselves as the “Reagan University,” the idea was scrapped. Instead, it was moved to the unassuming and quietly conservative town of Simi Valley where they could build a monument to Reagan. There, they could glorify his years in office, with only brief mentions of Iran-Contra or the AIDS epidemic, while leaving plenty of display space for Nancy’s many gowns.

It was easy to miss Grandma Prisbrey’s Bottle Village, as I did on my first solo trip out to Simi Valley. It’s on a non-descript frontage road that parallels the bustling Ronald Reagan freeway nearby. Unlike other grassroots environments built by men like Sabato Rhodia’s Watts Towers 60 miles south, or S. P. Dinsmoor’s Garden of Eden in Lucas, Kansas, Bottle Village is diminutive and unassuming. It doesn’t tower in the skyline like Watts, replicating the mastheads of famous Italian boats that Sabato saw as a boy back in Naples. It didn’t have Dinsmoor’s bravado to espouse his populist political views in concrete—depicting the working man being crucified by big business or building a mausoleum for himself where you could visit the artist perfectly embalmed for all to see.

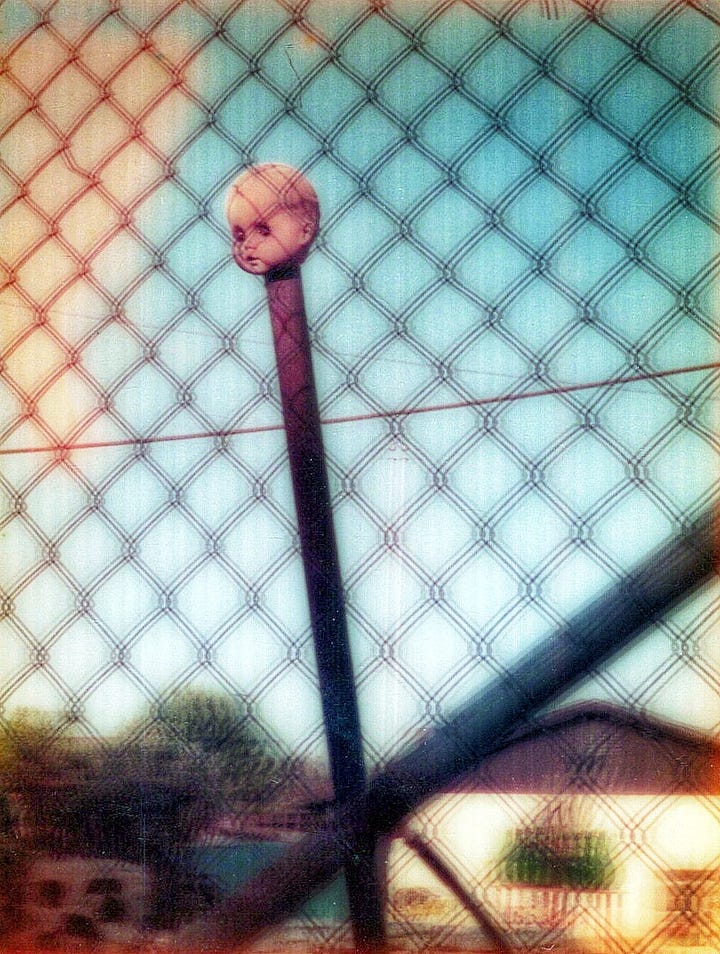

Tressa Prisbrey started her village with the simple premise, she needed somewhere to house her collection of 17,000 pencils. Well, that was the story she’d tell in documentaries made about her, or in the self-published brochure she gave out to visitors. But truth be told, she really built these bottle houses filled with light and color to protect and delight her remaining children, after losing four out of her seven to various illnesses. Her village was a labor of love, that turned into an obsession, continuing for 25 years, building 15 different structures and a variety of cement sculptures on her third of an acre lot including the Leaning Tower of Bottle Village, The Doll Head Shrine and The Round House. All this was to keep her remaining children happy, then later to fill her loneliness when her children moved away.

I never had the pleasure of meeting Grandma Prisbrey. By the time I made it out to Simi Valley in the late 80s, her health had deteriorated, and she had retired to Northern CA to be cared for by her daughter. When I did make the trek to Simi Valley, it was now boarded up and overgrown with brush. I crawled through a hole in the fence and cautiously made my way around this folk-art wonderland, where the pavement was lined with treasures Grandma Prisbrey had collected over the years from her many trips to the dump up the road. It was her own yellow brick road—with old license plates, toy guns, decorative glass all artfully arranged. Many of the buildings on her property were unenterable, so I peered in through windows, always to find a group of dolls inside, either dressed up by Grandma or their heads placed at that the end of poles as some kind of lookout. It was disturbing to say the least, the shock of dozens of glass or polymer eyes staring back at me. But after a while you get used to all those dolls, realizing each were carefully placed by Grandma with love. And with plenty of mirrors strategically placed in the houses, you’re constantly being reminded of your own reflection, where your eyes blend in with the hundreds of doll’s eyes around you. It is at this moment you realize you’ve become one with Bottle Village.

In her heyday, while she worked on her village, locals and tourists were always stopping by. She’d gladly take them on a tour of all her buildings and sculptures for twenty-five cents—pointing to such highlights as The Headlight Garden, a concrete planter she had assembled using car lights. She grew roses there, planting them for her daughter who loved this flower and was dying of cancer. As the story goes from Grandma, the roses died the day her daughter died. The tour would end with Grandma sitting at her piano, singing risqué songs she learned in the 1920s.

After visiting the place on my own, I began bringing friends to enter this other-worldly lot on the frontage road. Like clockwork, I missed it when I drove by, then having to make a U-turn after a few blocks ahead. I’d help my friends crawl between the fence, instructing them to be both careful and mindful when walking around, and not to force our way into any building we couldn’t open. Soon, my friends organized their own pilgrimages out there. On one such trip, a good friend of mine took her boyfriend, an MTV video director who was always searching for a new location. On returning from their mini road trip, the boyfriend thanked me for turning him on to such an incredible place, while describing how he was able to get into some of the closed off buildings.

“Oh, I just pushed the door open with my boots” he boasted.

Staring down at his black Doc Martins, I was horrified.

“Please don’t do that again” I urged him, hoping he’d find another location for his next video.

After that, I didn’t bring anyone out to Simi Valley, not returning there until thirty years later. But this grunge video director was the least of Bottle Village’s problems. The 1994 Northridge earthquake did a number on it. A preservation group called Preserve Bottle Village applied and won a FEMA grant—only to produce an immediate backlash by local politicians.

"How in the world can we spend half a million dollars on something no one wants?” said the State Representative and former mayor of Simi Valley who spearheaded the initiative to bulldoze the place down.

While Bottle Village’s grant support from FEMA was then severely downgraded, private supporters stepped up and donated additional money so that someday it could return to its original wonder. Because of these grassroots efforts, Bottle Village lives on.

I returned there myself with my youngest son in 2017. That is, after driving right by it again and making a U-turn up ahead. But there was no climbing through an opening in a fence this time. When we drove up, the woman who ran Preserve Bottle Village was already there, standing next to the now official National Landmark sign. As she showed us around, she continually weeded whatever vegetation that had crawled through the cracks in the sidewalk. This was the continuing mission of this grassroots society, giving tours when they could, replacing any broken bottles so the light could continue to shine through, and making sure the path was cleared to reveal Grandma Prisbrey’s sidewalk lined with gold.

***

If you want to see more of Bottle Village, there is a lovely short documentary about Grandma made in 1982, before she left her little world in the valley: Grandma's Bottle Village. In the film, Grandma is seen constantly walking around in her floppy sunhat, fixing and assembling things, or returning to the dump in her broken-down Studebaker to gather more bottles for her village. When she isn’t working, she sits down and sings a tawdry song from her early days. Throughout the film, she is always exclaiming the same phrase. It’s a catch-all phrase that she uses to describe a whole host of situations, from disbelief to wonder.

“Imagine that!” Grandma continually says.

Yes, imagine that.