A Passport to Nowhere

I received a piece of bittersweet mail recently; my new passport had arrived. It was usually issued in anticipation of a new trip ahead—an ocean liner to Europe in the 60s, flying down to Puerto Vallarta to get a terrible sunburn and diarrhea in the 70’s, or backpacking through Europe on a Eurail Pass in the 80s. Sometimes it had to be expedited because of an impending departure date or an unforeseen circumstance. But today, I had no reason for this expedited service. I have no concrete plans to travel outside this country. Putting in my new application was just some knee-jerk necessity, some precautionary measure to leave this country that I no longer want to be part of on its worst days. And there have been plenty of these worst days as of late.

But don’t get me wrong, I’ve never had a problem getting in and out of the country. I don’t have to defend my birthright citizenship, despite being born here. I’m not in danger of deportation, after exercising my first amendment rights and leading a protest against US policy. And I align with some norm that was checked off on a box when I was born. That is what makes getting a passport so bittersweet to me now.

Oh sure, I have skeletons in my closet like every American whose ancestors came here as immigrants—my Armenian grandparents coming from Iraq, or that my great uncle was a card-carrying communist back in the 1930s. Hell, my professor parents were card-carrying Atheists, and I drive a Subaru which stereotypes me as being a lesbian. But so far, no one is breaking down my door for the type of car I drive. Well, at least so far...

America has a long history of being arbitrary bouncers, flexing its muscle to control who can pass between the velvet ropes. Our government seems to skip over the part of the guest list where it’s written “all men are created equal.” 249 years later, we’re still parsing out these five words, still deciding who is worthy to come in and out of this country. Have we learned nothing from the mixed-up world of Dr. Seuss and his Star Bellied Sneetches?

“Now, the Star-Belly Sneetches had bellies with stars.

The Plain-Belly Sneetches had none upon thars.

Those stars weren’t so big. They were really so small.

You might think such a thing wouldn’t matter at all.

But, because they had stars, all the Star-Belly Sneetches would brag,

“We’re the best kind of Sneetch on the beaches.”

With their snoots in the air, they would sniff and they’d snort

“We’ll have nothing to do with the Plain-Belly sort!”

* * *

For my first passport at age four, the government skipped over the fact I hadn’t learned cursive yet and couldn’t sign my name on my passport. Not a problem, the government said, just have your mother sign it. Things weren’t as easy for my mom back in 1969. While she could sign my passport for me, she couldn’t sign up for her own credit card until 1974. US regulations then treated her no better than a four-year old, requiring her husband to be the primary signature if she wanted a credit card.

Things were just as easy during my teens. Having just turned 17, I backpacked through Europe on a Eurail pass, first on my own, then meeting up with my older brother and his girlfriend in Amsterdam. I got to Amsterdam a day early, wanting to do my own “sightseeing” that I was certain my more responsible brother didn’t want to do. I learned from a fellow backpacker about the Melkweg, a place not found in guidebooks, and they certainly didn’t serve milk as its Dutch name implied. Rather, this illustrious concert venue served more illicit and unpasteurized substances. With my map in hand, I navigated the streets, passing by the red-light district where neon club signs flashed in broken English things like “LIVE FUCKY FUCKY.”

But no fucky fucky for me today, I was on a mission to find a different kind of club. When I stopped to consult my foldout map, I heard a man’s muffled voice speaking to me. Maybe he’s checking if I needed help with directions to the Melkweg?, I innocently thought. He wasn’t. He spoke a bit louder, making sure I heard him this time.

“Give the man your money.”

I looked up from my map to find a group of young men surrounding me. They had circled around tight, making it impossible for anyone outside the circle to see in. Some of their faces looked vaguely like me with their scruffy beards, dark hair, dark eyes, and heavy brows. It was an unplaceable look—perhaps Middle Eastern or Southern European. Whatever their look was, it was extremely menacing now.

“Give the man your money,” the older man repeated. “Give the man your money or something worse will happen to you.”

I looked down to see a large knife, a knife long enough to gut a fish, but was now pointing inches away from my stomach. This wasn’t time to ponder what to do. Immediately, I gave over my wallet.

But that wasn’t enough.

“More,” instructed the man in charge, while the man with the knife pointed at each of my various pockets with the sharp end of his blade.

I emptied each one out and handed it all to him. First my Eurail Pass from one pocket. Then a small plastic wallet full of Amex Travelers Cheques from another. And then from my front pocket, my passport.

The man in charge grabbed it all. And with that, the circle dispersed, and they were gone. I stood there stunned and unable to breathe. I looked around to see if anyone nearby had seen that I had just been mugged. No, no one had. It was like it had never happened, with people passing to and fro, leisurely making their way home or out for dinner.

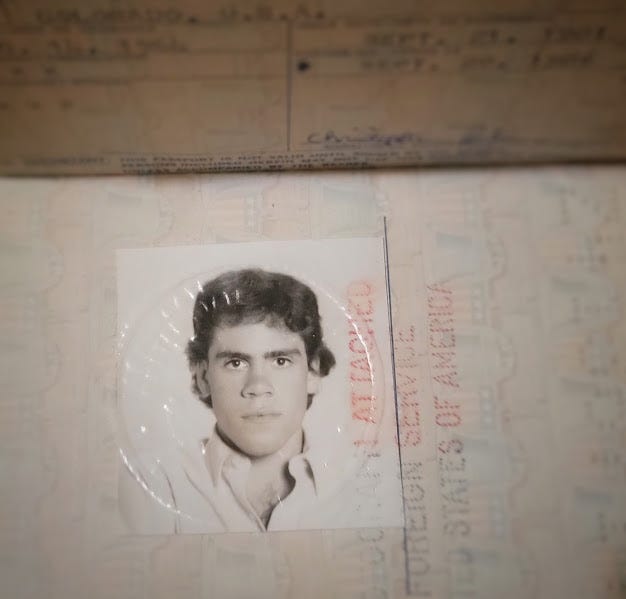

I turned back to see the thieves quickly receding in the distance. In that moment, I realized my whole existence was running away too. So, against my better judgement, I ran after them, hoping they’d drop it all when they had discovered there was little value in what they’d stolen. There was only a small bit of cash and a stash of traveler’s cheques that needed to be counter-signed and verified. My passport was no use to them either, issued a few years back and picturing me as a clean shaven fourteen-year-old American boy.

After running for a mile or so, I gave up, knowing I would never find them. What I did find was my emptied out blue Velcro wallet in some gutter. Well, it was not completely empty. For some unknown reason, they left me with a few favorite keepsake pictures and other mementos. While menacing, could these thieves be sentimental too?

When my brother arrived the next day, he looked at me very suspiciously as I recounted my harrowing ordeal. I didn’t understand why he was giving me the side-eye. I had made sure the story I told him omitted all references to the Melkweg. I was only “out sightseeing” when I was mugged, on my way to various standard tour spots found in any guidebook. Turns out, his issue was with my looks.

“You need to shave that beard off now, before we get your passport at the consulate,” he said and then continued with more stipulations. “And you should put on a button-down shirt too.”

While I was proud of growing my first beard, capitalizing on my Armenian genes to quickly grow copious amounts of hair, I reluctantly knew he was right. Problem was, I had thrown away my razor a week or so before. So instead, I borrowed his girlfriend’s dull pink plastic lady razor. In the bathroom, splashing water was of little help, it didn’t take away the sting of removing a week and a half’s worth of scruff with this semi-useless razor. I then searched through the bottom of my backpack, finding the one dress shirt my father insisted I pack “just in case.” In his mind, my bon-vivant father was certain we’d dine at Michelin-starred restaurants every night, while backpacking from youth hostel to youth hostel.

When arriving at the US consulate, we joined a group of various Americans already waiting. By the way they slumped in their chairs, it appeared they’d been there for a while. They looked like older versions of me in varying degrees, but with much longer hair and more substantial beards. I thought to myself, I’m sure they’ve been to the Melkweg many times. But now I no longer looked like them, my face was clean-shaven and slightly red and nicked. I looked less like an intrepid traveler, and more like I would be playing in some band recital in my button-downed oxford and khakis.

When it was my turn to see the Consulate General, it was a brief meeting. I presented him with my youth hostel card, the only identification I still had, from when I checked in at the hostel. This ID was far from anything official. It had a picture of me stapled to it, with scant information typed out on the card itself. The Consulate General looked up from the card and to me in my white dress shirt and red shaven face. After a few perfunctory questions, he handed back my flimsy card.

“It will be ready in 30 minutes, maybe less.”

I returned to the waiting room and waited with all the older guys in their t-shirts and torn jeans. But before I knew it, the Consulate General’s secretary came out and handed me my brand-new passport. I nodded to the guys as I left. They nodded too, then sank back into their chairs, not knowing when they would leave.

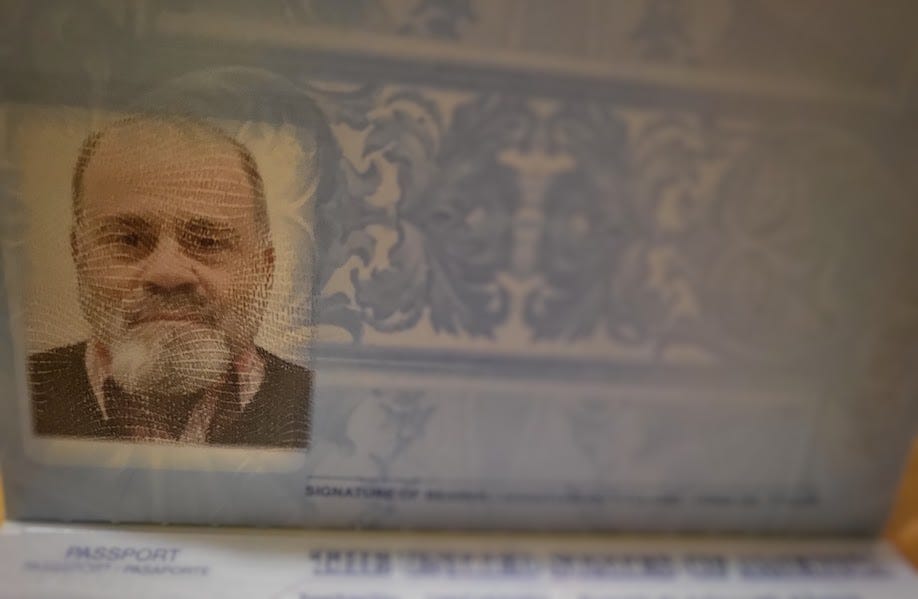

40 some years later, and many passports in between, it was even easier to get my most recent passport. With a few clicks online, I loaded my picture where I proudly sported a more substantial beard than in my backpacking days. Despite looking increasingly more ethnic like my immigrant ancestors, I’ll take my chances. I am heartbreakingly aware how my removable facial hair is a luxury and is purely arbitrary. This luxury isn’t the case for those dear to me. They’re unable to get this same document, not conforming to some norm and checked box, despite what was written about equality by a bunch of wig-wearing men 249 years ago. I can’t even sign my son’s picture and make everything ok.

As I come to the end of this blog, I’m again at a loss. With each new post, I find this country closer to the edge, closer to giving up on the golden rule, and closer to giving away our power to a man who likes to be surrounded by gold.

I can’t make that leap of faith here, neatly tying everything up at the end. There’ll be no Blanche DuBois moment, there will be no believing in “the kindness of strangers,” as she is being carted away to some mental ward by a doctor. I am also having a hard time locating that amazing altruism that Anne Frank had, that “despite it all” grace and goodness she saw in humanity.

Standing over the precipice of this mixed-up country, I’ll just settle for a fictional picture book ending, from a doctor who wasn’t really a doctor.

“The Sneetches got really quite smart on that day.

The day they decided that Sneetches are Sneetches.

And no kind of Sneetch is the best on the beaches.

That day, all the Sneetches forgot about stars and whether They had one, or not, upon thars.”-Dr Seuss